Synopsis from Goodreads:

When Alice’s father goes down in a shipwreck, she is sent to live with her uncle Geryon–an uncle she’s never heard of and knows nothing about. He lives in an enormous manor with a massive library that is off-limits to Alice. But then she meets a talking cat. And even for a rule-follower, when a talking cat sneaks you into a forbidden library and introduces you to an arrogant boy who dares you to open a book, it’s hard to resist. Especially if you’re a reader to begin with. Soon Alice finds herself INSIDE the book, and the only way out is to defeat the creature imprisoned within.

It seems her uncle is more than he says he is. But then so is Alice.

Much later, Alice would wonder what might have happened if she’d gone to bed when she was supposed to. (Page 1, Chapter 1)

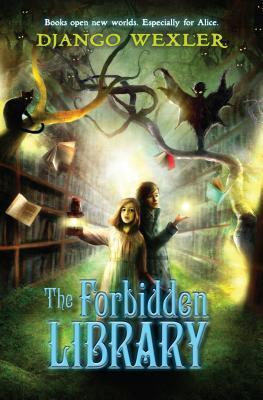

This is the opening line in Django Wexler’s new middle grade fantasy, The Forbidden Library. The first in what will be a series of books, this sentence sets the tone for the rest of the story, which often keeps the reader wondering what’s going to happen next.

The Setting

Something that sets The Forbidden Library apart from many other modern middle grade fantasies I’ve read is the fact that it takes place in the past, during Hoover’s Presidential term in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s. It was a daring move for a story aimed at a young contemporary audience that won’t readily identify with the period, especially when it comes to the lack of technology (they still use gas lamps.)

Wexler’s choice to set the story in the past appealed to me, however. I believe the magic books in Geryon’s library, as well as the vibrant characters and intriguing plot twists, are sufficient to hold a middle grader’s interest, and the time in which the story takes place might inspire children to buff up on their history.

The Characters

Our protagonist Alice, a precocious girl who likes to read, does well in school and strives always to be on her best behavior, serves as a role model for Wexler’s middle grade audience, especially when compared with other less savory characters, each of whom leave the reader to wonder by the end if there’s anyone poor Alice can trust.

Her companion as she explores the library in search of the fairy Vespidian, believed to be responsible for her father’s death at sea, is a talking cat named Ashes, a creature reminiscent of both the cat from Neil Gaiman’s Coraline and the Cheshire Cat from Lewis Caroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Being a fluent speaker of sarcasm, I could very much appreciate his wry and usually condescending tone toward Alice, and was often unable to suppress a smile. Yet, sometimes I also thought it was over the top. In one memorable exchange regarding Ashes’ views on the nature of death, I felt like I was watching the famous Dead Parrot skit from Monty Python’s Flying Circus (pay particular attention to 2:35 – 2:50.)

All the characters were vividly described, and I found their behavior to be realistic. There were no heroes (save for Alice and her father), but aside from the fairy Vespidian or Mr. Black, there were no absolute villains either. Though some were obviously more dubious than others, every character exhibited both decent and not-so-decent qualities. They were believable for the same reason that Rowling’s characters in Harry Potter were believable: their humanity, with all of their flaws and imperfections.

There was so much subterfuge that during the course of my reading, I would think I’d figured out a character’s motivations, only to discover a few pages or a few chapters later that I was mistaken. By the end, I could only feel sorry for Alice, who’s been thrust into a dangerous game saturated with competing agendas and zealous self-interest.

One thing that impressed me about Alice’s character was her conscience. In her forced encounters inside prison books, worlds accessible only to Readers, in which dangerous creatures were imprisoned long ago, creatures that must be bested and consequently bound to the victorious Reader if the Reader is to survive the journey inside, Alice would first attempt to win through cool-headed reason and argument, and would only ever kill as a last resort, though killing was the normal course of action for every other Reader. And then, after she’d bound a creature to her will, she’d only ask it to do something dangerous when absolutely necessary, and would always do her best to avoid allowing it to experience pain, an attitude that was also at odds with the means by which the same creatures were employed by Geryon and the other Readers. It further cements Alice’s role as a hero and a model for children to look up to, teaching them that those in positions of great power should be the most humble and charitable of us all.

Reading as Magic.

What drives this particular fantasy is the conceit that books are special, that they literally contain magic, accessible only to a special class of people called Readers. Some are portal books, which transport Readers from one place to another. Others are prison books, which contain dangerous creatures that were locked away forever during their book’s creation.

The magic inherent to Reading is an allegory for the power of words, stories and the imagination. It allows both children and adults to approach something that’s ordinary and mundane on the surface from a different angle, from the vantage point of the extraordinary, so that reading is made exciting once more.

Writing and Style.

Wexler has sarcasm and dry humor down to an art. From the way he features the lawyers and accountants who descend on Alice’s father’s estate like vultures the moment he’s lost at sea, to the way he playfully describes otherwise ordinary objects and sounds, I was blown away by how witty and clever the writing was. Just a heads up: if you don’t appreciate sarcastic humor, you probably won’t enjoy this book.

The story’s pace pairs well with the plot. When the reader should stop to take a look around, things slow down, and we’re presented with many fine details that paint a beautiful picture that make the world come alive. When the reader should feel tension and suspense, things speed up, so that the reader is caught up in the fervor of conflict and can’t put the book down until things are finally resolved. In either case, there was never a point where I felt that the story dragged, or where I felt that the story should have slowed down. Like the last bowl of porridge in Goldilocks and the Three Bears, it was just right.

I often found myself comparing various passages to poetry, and discovered that Wexler’s very creative when it comes to the use of simile. Below are some specific sentences that stood out to me:

…and after the accountants, like a Biblical plague building up to a big finish, came the lawyers. (Page 16, Chapter 2)

Again the silence, as though the conversation had fallen into a pot hole. (Page 35, Chapter 3)

The flame flickered weakly…, like a caged spirit. (Page 51, Chapter 5)

Each gust of wind brought a rush of whispering leaves, rising and falling like the sound of surf on a beach. (Page 71, Chapter 6)

Wexler also peppers in some great vocabulary words, just enough that it always comes off as natural and unobtrusive. As a lover of words, I could appreciate his approach, and I’m hopeful that kids will make the effort to look them up. Here are just a few of the words that I enjoyed: avuncular, plinth, hermitage, vanguard, tureen and scrupulous. I tried to write them all down, but I was so caught up in what I was reading that after the first few chapters I lost track.

Other Thoughts.

The books in The Forbidden Library reminded me a lot of the 1994 computer game Myst, which contained both “linking books,” which transported explorers from one world to another, and books in which people could be imprisoned. I also detected significant influences from Harry Potter — when Alice passes through the wall of the library just like Harry at King’s Cross Station — Coraline and Alice in Wonderland.

Wexler used the Swarm, Alice’s first bound entity, to come up with some creative solutions to otherwise difficult problems. In particular, I would watch out for how Alice approaches her final prison book’s adversary.

There’s a lot of foreshadowing, from the very first sentence to things that hint at events to come in future books. During Alice’s final confrontation, it’s strongly implied that she has a unique ability that I suspect will come into play again in either the next book or in one further down the road.

There were times when I was confused, or when I felt that something was not adequately explained. I thought, for example, that Alice’s encounter with her essence should have been expounded on. I found myself asking why the experience of gazing upon one’s own essence should be so painful, but only during the first time, and I never received a satisfactory answer. I was also unclear as to whether or not her father, who appeared to Alice in a dream, was really just a product of her subconscious mind or if her father had found some way to communicate with her.

I loved the transitions between the opening of a book, when Alice would start reading, and the beginning of Alice’s experience inside the book, both of which employed the same first sentences, linking the two together beautifully.

Finally, in exploring the nature of the creatures bound up inside prison books, some fascinating existential themes arise that will appeal to the story’s older audience.

Conclusion.

The Forbidden Library is an enjoyable, unique and well-written tale with a satisfying climactic ending that answers just enough questions to provide relief, but leaves enough mysteries unsolved that the reader will be left eagerly anticipating the next book in the series.

I enthusiastically recommend The Forbidden Library to children and adults, and give this one four out of five stars.

Enter your email address and click "Submit" to subscribe and receive The Sign.